Christian Universalism

John Murray

(December 10, 1741-September 3, 1815)

If Christian Universalists had a bishop, it would be John Murray. And although we don’t John Murray has become the face of Christian Universalism, and recognized as the “Father of the Christian Universalist Church.” For the last three decades of the 18th century, the English-born, Boston resident, was certainly the best know, and most widely-respected American Universalist.

There are many excellent essays written about Murray and his role in establishing the Universalist Church, and rather than repasting them, this essay will briefly touch upon his role and theology.

We’ll begin not with the beginning, but the establishment of America’s first Universalist Church and the beginnings of a denomination. However, before we do, we need to digress to 1770 and a run-aground brig off of the coast of New Jersey. Seventeen-seventy is considered the year that Christian Universalism was first preached on American shores, at least that is the date that the Universalist Church claims. The story goes that the brig Murray boarded to emigrant to America ran aground and Murray was sent to shore to secure food. On shore he met Thomas Potter, a Rogerine Baptist, a universalist sect. Potter upon finding out that Murray was a preacher and a universalist, enlisted Murray to preach while the ship was aground. He did so, but universalism was not the content of his preaching. That didn’t happen until he began preaching in New England.

While in New England he met the influential businessman, Winthrop Sargent, a Universalist, who invited him to preach in Gloucester, MA. [He later married Sargent's daughter, the influential universalist poet and writer, Judith Sargent.] In Gloucester a growing group began to assemble to hear his preaching and to worship, and soon ran into legal problems with the establish church, the Congregationalist. Not only for his theology, but because those attending Murray’s gatherings resisted paying the required parish tax. They reasoned why should they, they weren’t attending the Congregational Church.

The church was sanctioned and seized, along with the personal property of members, for withholding the tax. In turn the Universalist sued on the basis of the Bill of rights and the 1780 Massachusetts Constitution. The trail dragged on from 1783 to 1786, when the court ruled in favor of the Universalists. Oddly, Murray did little personally to move the trail forward and only reluctantly allowed his name to be used, rather preferring the laity to respond to the charge.

The settling of the case in favor of the “Free Church of Gloucester” allowed him to freely begin his efforts to unite the various Universalist societies into one denomination. Although the Gloucester church is considered the first Universalist Church it was not until the 1790s that the local societies of Christian Universalists began to truly unite.

In 1785 Murray became acquainted with Oxford Universalism and traveled to Oxford (MA) several times. With Elhanan Winxhester, the founder of Philadelphia Universalism, Murray tried to establish a regular convention of New England Universalists. The Oxford convention had a rough start and faltered, but it did encourage Universalists elsewhere to form their own conventions. How much faltering had to do with Murray’s dislike of the theology of the Oxford Universalist is open to question. Murray had reservations about the theology of Winchester and the Philadelphia Universalists too. Nevertheless, he felt more at home with them than he did with those of New England.

In 1790, the longer-lived Philadelphia “Convention of the Universalist Church” was organized by Murray and Winchester, and Murray found a spiritual home. 1n 1793, a “New England delegation” (more than likely Murray) asked the Philadelphia Convention for permission to organize a New England Convention. That convention, chaired by Murray, became the nucleus of the United States General Convention.

Following this Murray returned to England for a visit. Upon arriving back, he returned to Boston and the Universalist Church he had helped to establish. Associated with a prestigious urban church became the face of Universalism in America.

Conversion to Universalism:

While living in Ireland, after falling out with his mother, Murray met George Whitefield who was conducting a revival. Being a young preacher (he started preaching in his teens) Murray was attracted to Whitefield’s Calvinism. After which he tried preaching in Whitefield’s Irish pulpit, but met opposition and left for England where he attended Whitefield’s Tabernacle. While in England, during a period of financial debt, Murray experienced a sense of lostness.

During this period, James Relly, who had been associated with Whitefield’s Tabernacle, published his Union, a book expounding universal salvation. Relly’s view was that every human participated in a mystical union as part of the body of Christ, and as part of the body, would not be lost. The idea appealed to many and the doctrine spread, much to the annoyance of the Calvinist. Whitefield, along with other Calvinists set out to “rescue” those taken up and deceived by universalist thinking. Murray was one of those sent. Sent to “rescue” a young woman, he was taken with her argument and began to study Relly’s works, looking to find the flaw in Relly’s arguments. He couldn’t and became a supporter of the idea of universal salvation, and was removed from Tabernacle membership.

Feeling disconnected, Murray eventually emigrated to New England, and in time the Christian Universalist Church was born.

Theology:

Murray was a Trinitarian, although an unorthodox one, believing that god had various “faces” (modes)—Christ, the human face of God (with the double nature of both human and wholly God).

Fairly Orthodox in other matters Murray held to original sin and vicarious atonement. He believed that the sin of humankind against the majesty of God was infinite and could only be expiated by Christ, who being God, could do so infinitely.

Those who dies unrepentant would, according to Murray, be punished in the afterlife until the Day of Judgement, at which time all humans, as part of the mystical body of Christ.

Murray was a Trinitarian, but not an orthodox one. Like the ancient Sabellian heretics, he portrayed God as having various modes or faces. Thus Christ is the human face of God. Christ is not, however, a mere human, but a double-natured being that contains the wholeness of God.

Murray was fairly orthodox in his teaching on original sin and vicarious atonement. He believed that the sin of mankind against the majesty of God was infinite; therefore, it could only be expiated by Christ, who, being God, could do so infinitely.

Murray believed that those who died impenitent would be punished in the afterlife until the Day of Judgment. At the Last Judgment, all human beings, as part of the mystical body of Christ, would be found to have t heir names written in the Book of Life. Thus, all would ultimately be saved. Satan, fallen angles and demons would be condemned. His theology of afterlife punishment was based on his interpretation of Matthew 25, the separation of the sheep and goats. For Murray, is ultimately all people where sheep, the goats were the demons found in all people. Murray acknowledged that his doctrine of evil was not well-accepted by other Universalists.

Reference Sources:

"John Murray," Dictionary of Unitarian & Universalist Biography [External Link]

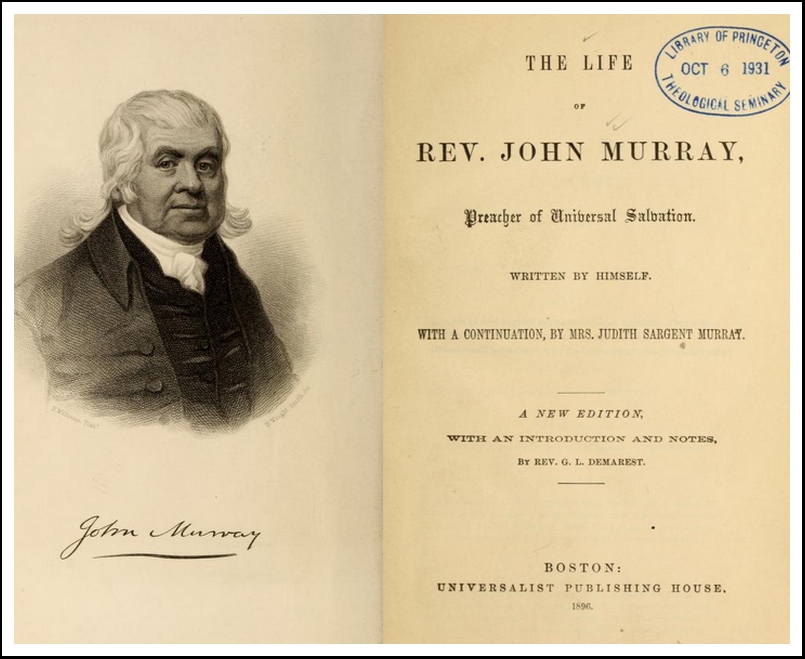

The Life of Rev. John Murray, Late Minister of the Reconciliation, Preacher of Universal Salvation. His autobiography is his most famous work, offering a profound spiritual narrative and insight into the early American religious landscape. [PDF Copy]

Continuation by Judith Sargent Murray: His wife, Judith Sargent Murray, provided a continuation of his life and work after his death, adding further context and historical depth.

Sermons and Tracts: Murray authored numerous sermons and theological tracts advocating for the doctrine of universal salvation, which were central to establishing the Universalist denomination in America.