A Miniscule Seed & An Outcast

A Sermon | May 18, 2025

First Presbyterian Church

Sandusky, OH

<

<Micah 6:1-8, Mark 4:26-33, Luke 10: 25-37

This morning, we want to look at two of Jesus’ parables: The Parable of the Mustard Seed and the Parable of the Good Samaritan—a parable about a miniscule seed and a despised outcast. At first glance they seem to be unrelated. What does a miniscule seed have to do with an outcast?

I suggest, everything.

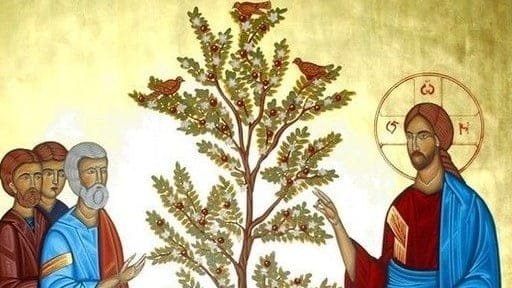

Let’s begin with the Parable of the Mustard Seed:

As with all of Jesus’ parables there are numerous interpretations of the Parable of the Mustard Seed. Some see the seed as scripture. Sometimes taking root, other times not. Some interpret the mustard seed as the work of the Holy Spirit, whose work sometimes does not bear fruit. Others equate the mustard seed to Christians. Some grow into the faith quickly. Others slowly. And still others see the mustard seed as an allegory of the church yet to come. The problem with all of these and similar interpretations is twofold. First, they make the parable into an allegory. And secondly, they impose preconceived doctrine upon the interpretation.

Note how Jesus started the parable, “The Kingdom of Heaven is like the mustard seed.” The word “like” is the key to understanding not only this parable, along with all the others. “Like” implies that each story is, or contains, a metaphor for how, or what the Kingdom of heaven is. In this parable, the Kingdom of Heaven is like a miniscule mustard seed that has grown into a large shrub. Providing even protection for wild birds.

However we interpret this parable, it must say something about the Kingdom of Heaven. Jesus says that the Kingdom of God is within us. He also says that it is present in the here and now. What that means is (1) that we are the physical manifestation of God’s presence in the world. And (2) we can sense (if we seek it) the divine presence in all of Creation.

Through parables Jesus taught his disciples and likewise teaches us what it means to (1) be the manifestation of the Kingdom of God, and (2) what it means to be in the midst of the Kingdom of God, e.g., Creation. Jesus’ parables always point to everyday life.

Let’s look at the parable of the Mustard Seed:

In Jesus’ day, no one would intentionally plant a mustard seed. In fact. The Jewish Mishnah (compiled exegetical interpretation of Jewish law) forbade the growing of mustard in the garden, because they were “useless annoying seeds.”

In this parable the birds of the air come and nest in the mustard shrub. In the Hebrew scriptures the “birds of the air” are often a reference to outsiders, foreigners, who were considered “unworthy.” The Kingdom of Heaven is expansive enough for everyone, even the outcasts, even those who think or act differently.

The disciples, and by extension, we Christians, should never consider ourselves above anyone, as do the Pharisees and other Jewish leaders, and sadly, many Christians.

There is another lesson in the parable. The mustard seed is the Kingdom of Heaven—and so are we.

No matter how insignificant we think we are we are the seeds of the Kingdom of Heaven. We never know what the smallest, most insignificant gesture of care might sow. If we should never consider ourselves better than another, does this not imply that all are our neighbors, even the so-called unworthy?

Which brings us to the Parable of Good Samaritan:

Like the Parable of the Mustard Seed, the Parable of the Good Samaritan has been interpreted in numerous ways. Following our premise that a parable is a metaphor for the Kingdom of God, we ask, what does the Good Samaritan have to say about the Kingdom of God here in the present?

The old Christian Universalist Church had as their faith statement a simple one, “Love is the Way.”

And this is the context of the Good Samaritan: A Jewish Leader comes to Jesus and asks, “What is required to inherit eternal life?” Jesus replies, “What does the scripture say?” The leader answered correctly, “Love the Lord with all of your soul, and with all of your heart, and with all of your mind. And, love your neighbor as yourself.” To which Jesus replies, “Exactly, do this and you will have eternal life.”

But then wishing to excuse himself, the leader says, “But who is my neighbor? That’s kind of hard to figure out.” Reminds me of the minister I heard the other day, in all seriousness, say, “That was for Jesus’ time. Doesn’t apply now. It’s far too hard to love our neighbor.”

We are all familiar with the story: A priest (or archbishop), the rabbi (or the minister) come upon a man who has been beaten, robbed and left by the side of the road to die. They saw him, then crossed the road and passed by. Because the man was wounded and bleeding, he was unclean, and thus, unworthy of their attention. Then along comes the despised Samaritan – himself unworthy in the eyes of a Jew – and took it upon himself to help the wounded man, who even to the Samaritan would have been unclean.

[Samaritans were what we would call today, a cult. They were ethnically related to the Israelites. When Israel came under the Assyrians, the Northern Kingdom Israelites in the area of Samaria, did not. The Samaritans believed that the Torah became corrupted under the Assyrians, and that theirs was still pure and true to the original. The Hebrews, naturally thought that theirs was correct, and thus despised the Samaritans.]

Back to the story: The Samaritan came along, took pity on the wounded man, bound up his wounds, took him to an inn, which in those days, also might function as a hospice. Paid for his lodging and medical care in advance. Telling the innkeeper if he needed more, he would settle up on his return.

Then Jesus asked the Hebrew leader, “Which of the three was the neighbor?”

There is an interesting twist here: The scripture says, “Love your neighbor as yourself.” Jesus makes the Samaritan the neighbor, even though he had no previous contact with the wounded man. He also implies that the wounded man was just as much the neighbor as the Samaritan.

In the old Pogo comic strip, we hear Pogo saying, “I have met the enemy and he is me.” I suggest Jesus is saying, “You have met your neighbor, and he is you.”

Does not Jesus urge us to love our neighbor as ourself?

The Samaritan could have ridden on by, but he chose not to. He stopped to see if there was a need, and then he acted, providing for the wounded man’s well-being.

I suggest that when the Samaritan stopped, he became the mustard seed and his act became the mustard plant providing care for the “unclean-unworthy.”

The Gospel of Matthew records Jesus saying, “Who ever cares for the most marginalized and vulnerable, cares for him. The wounded man was encountered along the road, not in the synagogue. And though we may indeed encounter those in need in the church, most will be found on the side streets of life. And it is on the side streets of life that the Kingdom of God is most active--- and most needed.

The Prophet Micah said, “What does the Lord your God require of you? (The Lord your God) requires just living, merciful acts, wrapped in compassion and humility.” It is through the planting of these “mustard seeds” that we love our neighbor as ourself.

May God grant us the Holy Wisdom to hear and apply. Amen.